THE ALL COUNTRY

PRESERVATIVE(S) LOVE COMPETITION

ENTRANT # 10,692,4759

(out of 11,000,000)

When a person is a baby and child, parents provide the container through which the child can become itself. Protecting the child from harm through acts of repetition, safety, and nurturing, children are held in a space of possibility and potential, a space that will eventually, over time, be filled with their identity.

This is referred to as preservative love.

With dementia and dementia caregiving, it is the opposite. Preservative love in dementia protects the dementia patient from both physical and moral harm, including the harm of loss of identity. It is a container through which the caregiver attempts to hold in the identity that used to be, an identity that, in time and with a guarantee, vanishes.

These durational repetitive acts of care and emotional labor in dementia caregiving can go on for years, even decades.

In attempting to preserve a vanishing identity, family dementia caregivers often lose their identity in the process.

Often doing it alone, family dementia caregivers do not have anyone helping to preserve their own identity, and with this, dementia vanishes the identity of not one, but two people at the same time.

When the caregiver’s identity vanishes, their ability to provide preservative love and retain and contain the identity of their loved suffers as well.

Inspired by county jams and preservatives competitions, I have created The All-Country Preservative(s) Love Competition, where caregivers display the preservative love they have provided for their loved one with throughout the years.

Below is Caregiver #10,692,4759 entries.

See what the judges have to say and her final competition ranking.

Year 2 Entry

In her first ever entrance to the competition, after providing two years of preservative love, this caregiver nails it. The caregiver is really preserving the identity of the person she cares for in spectacular fashion. Blue ribbon!

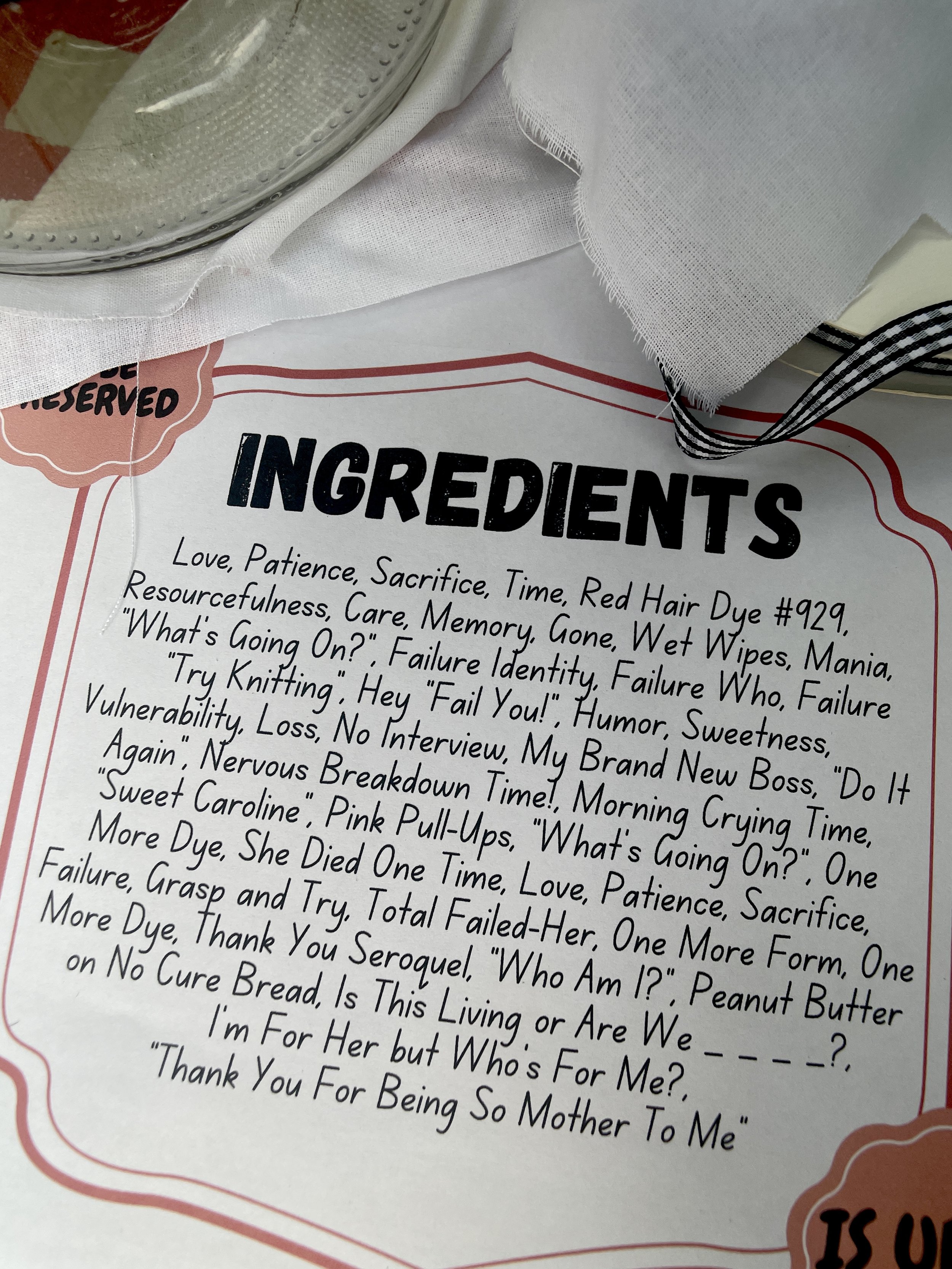

INGREDIENTS LIST

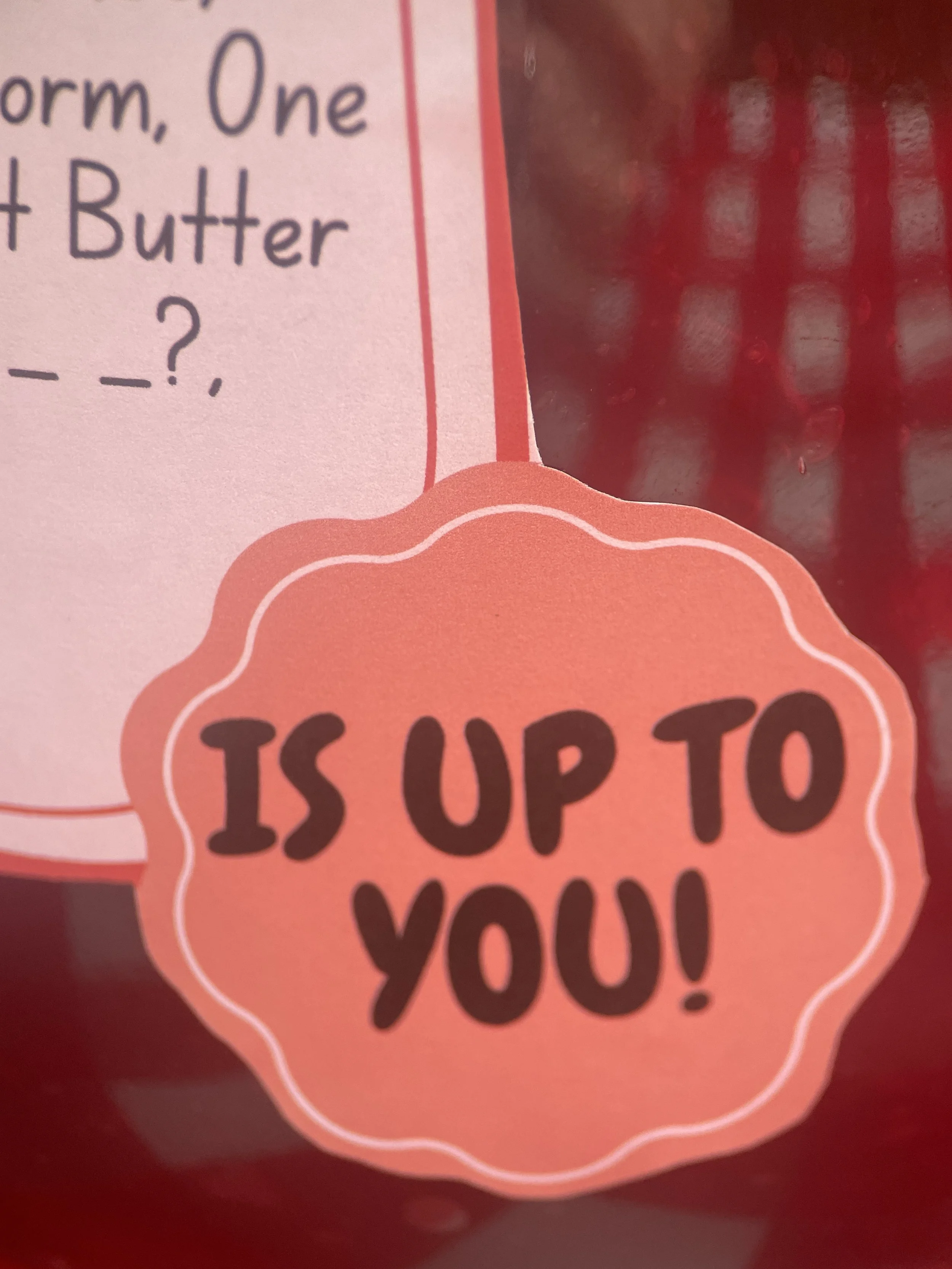

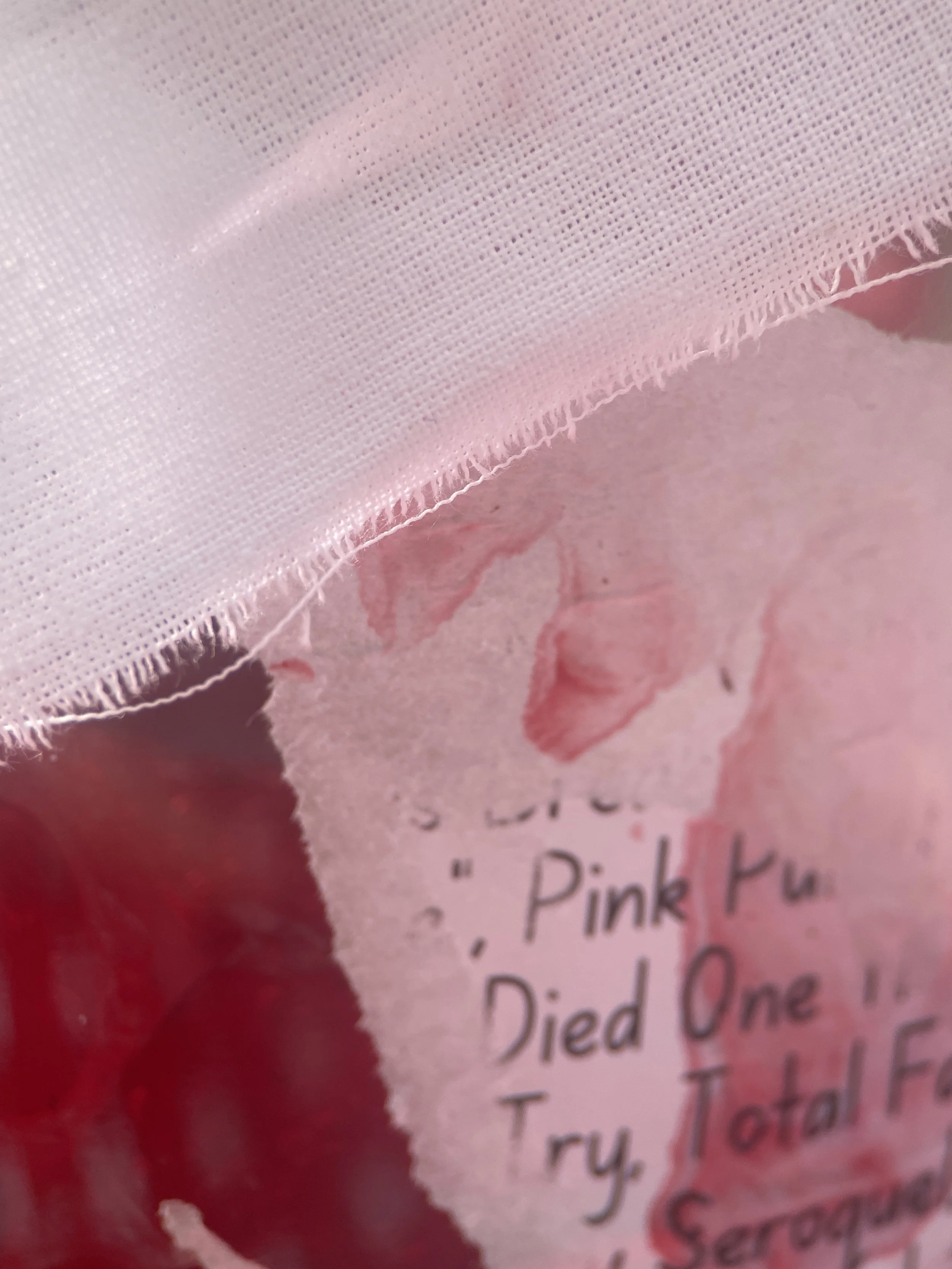

Love, Patience, Sacrifice, Time, Red Hair Dye #929, Resourcefulness, Care, Memory, Gone, Wet Wipes, Mania, “What’s Going On?”, Failure Identity, Failure Who, Failure “Try Knitting”, Hey “Fail You!”, Humor, Sweetness, Vulnerability, Loss, No Interview, My Brand New Boss, “Do It Again”, Nervous Breakdown Time!, Morning Crying Time, “Sweet Caroline”, Pink Pull-Ups, “What’s Going On?”, One More Dye, She Died One Time, Love, Patience, Sacrifice, Failure, Grasp and Try, Total Failed-Her, One More Form, One More Dye, Thank You Seroquel, “Who Am I?”, Peanut Butter on No Cure Bread, Is This Living or Are We _ _ _ _?, I’m For Her but Who’s For Me?, “Thank You For Being So Mother To Me”

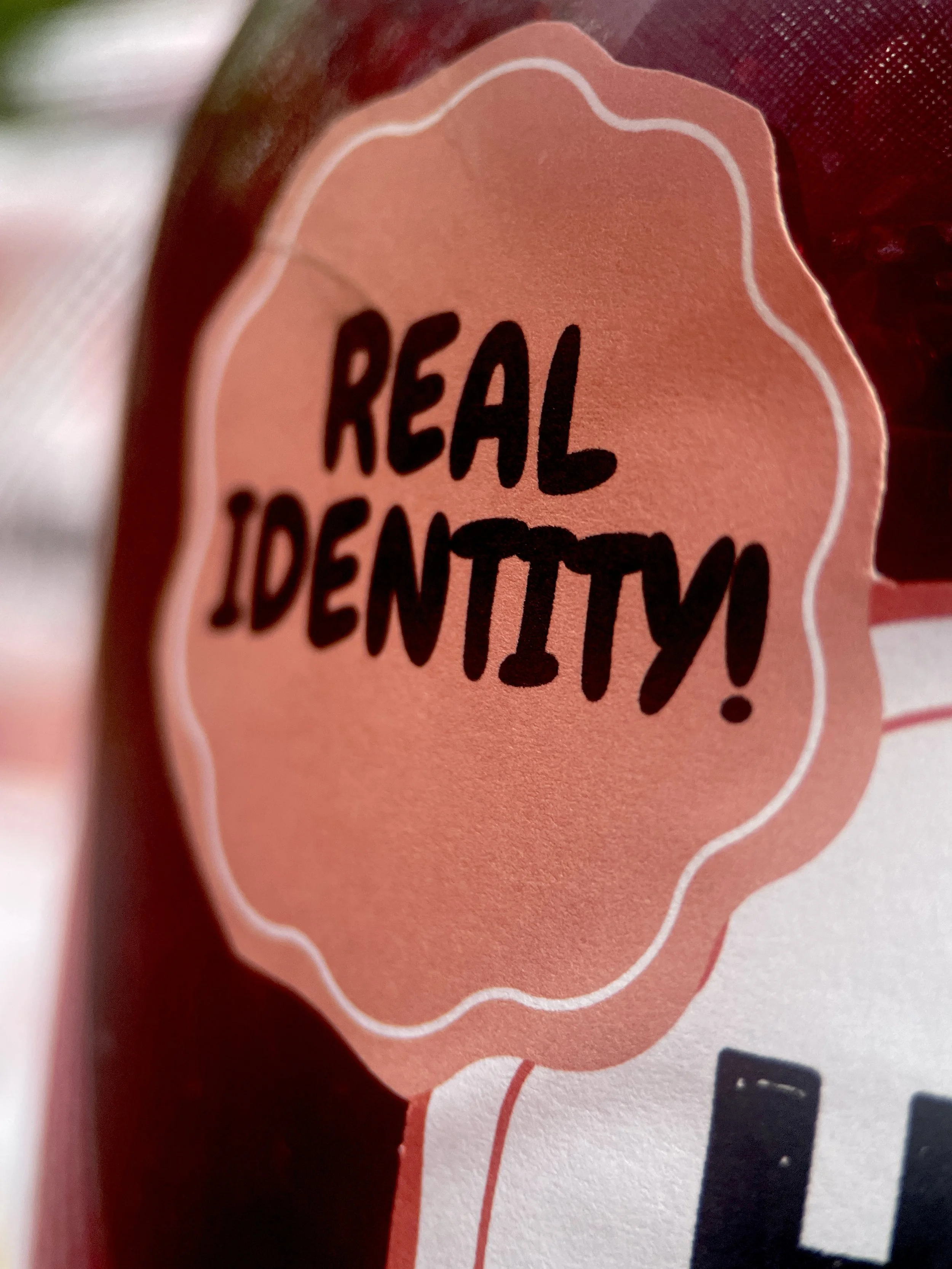

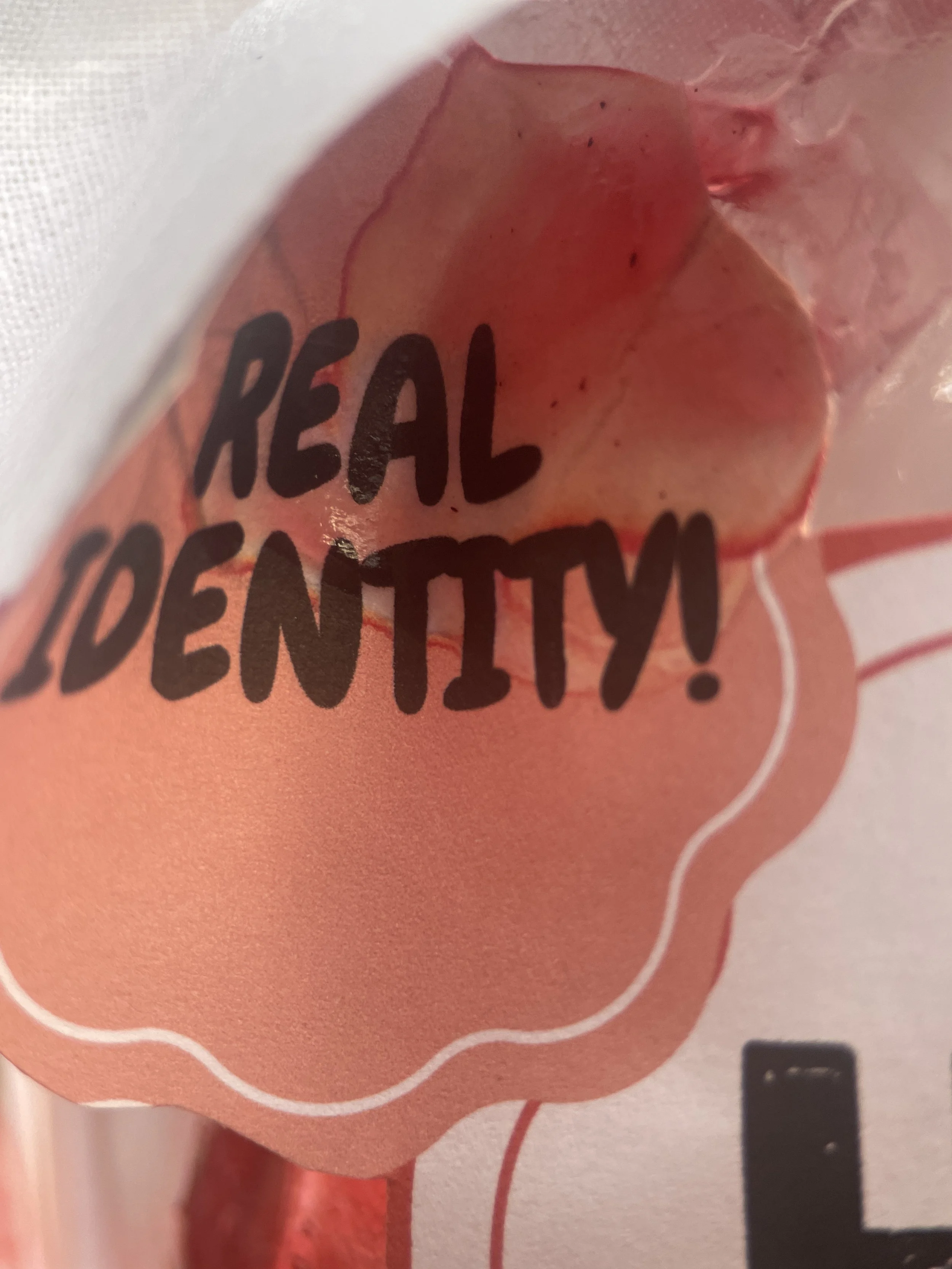

Made with real dignity, real identity!

Year 4 Entry

As you can see, this caregiver had some struggles this year. Too bad. Some real potential but she misses the mark. She wasn’t able to fill the jar, and those refined details that really preserve identity just aren’t there. Better luck next time caregiver!

Year 6 Entry

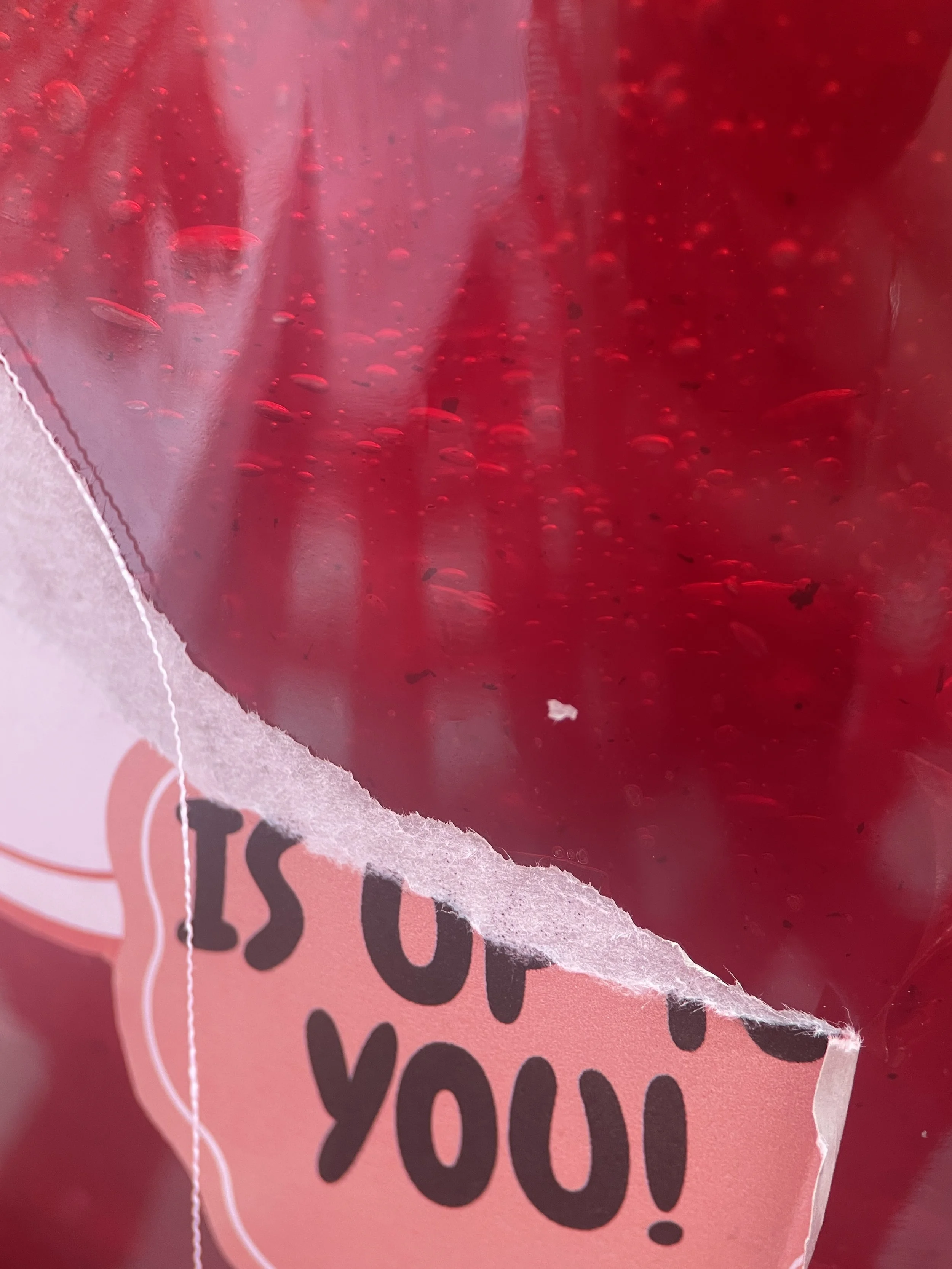

Oof! This caregiver had a tough break this year, literally. The jar broke and is a complete mess. It’s almost not judgeable but we will! It doesn’t even look like it was put together well to begin with. There are typos on the display card, and it looks like she got mad and crumpled the card up before placing it. Who does that? And with all that glass? Makes me question her safety protocols.

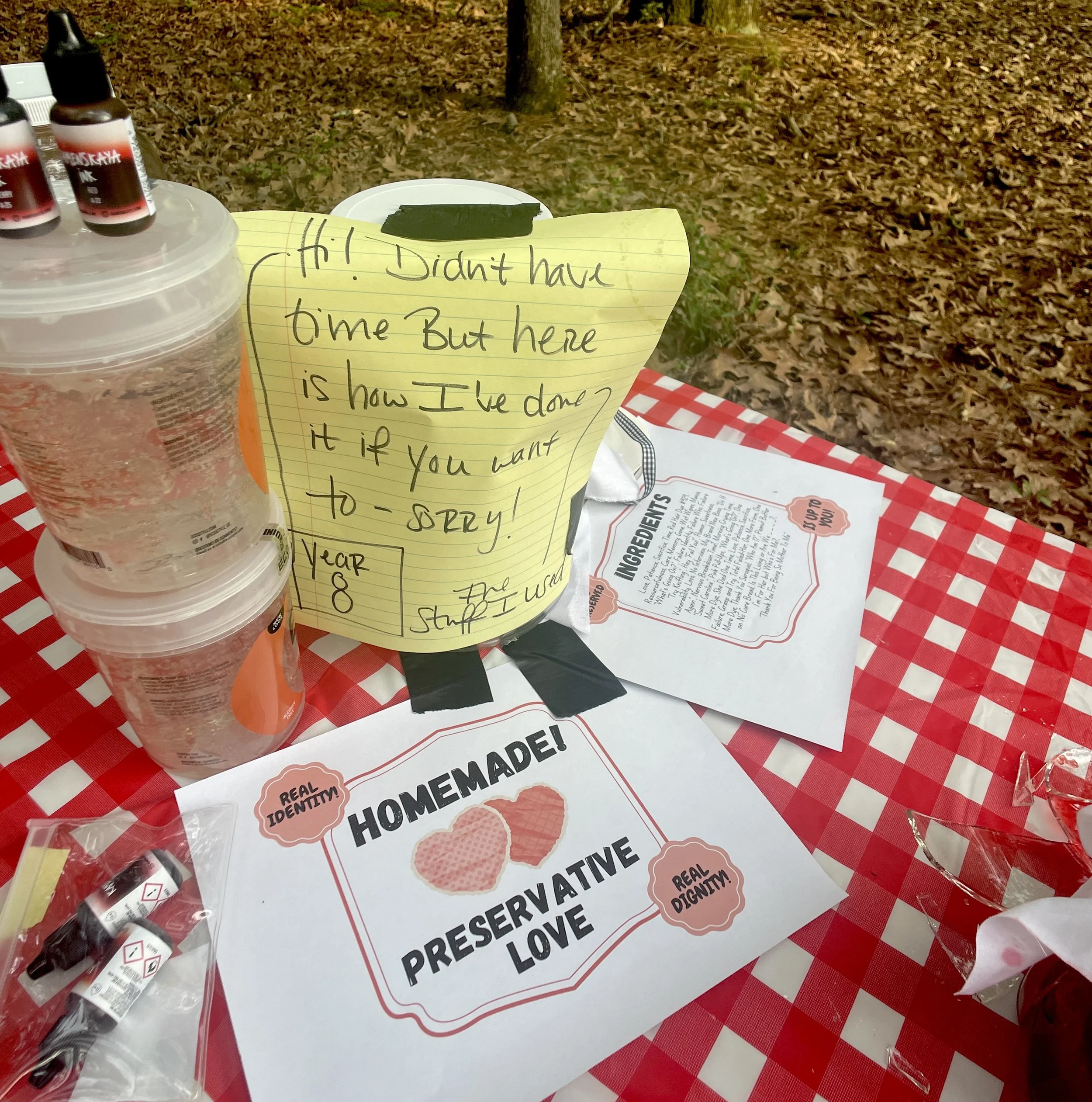

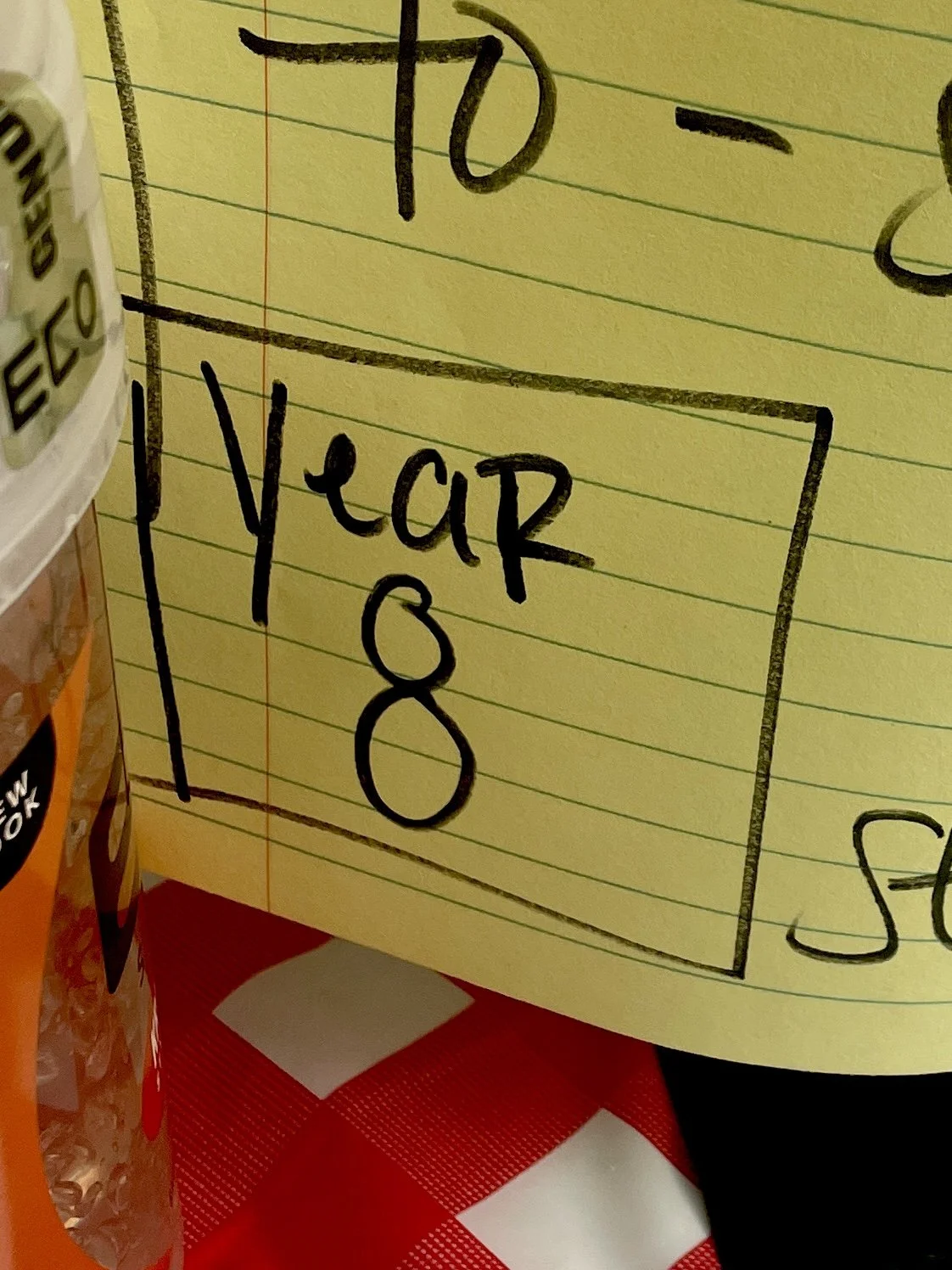

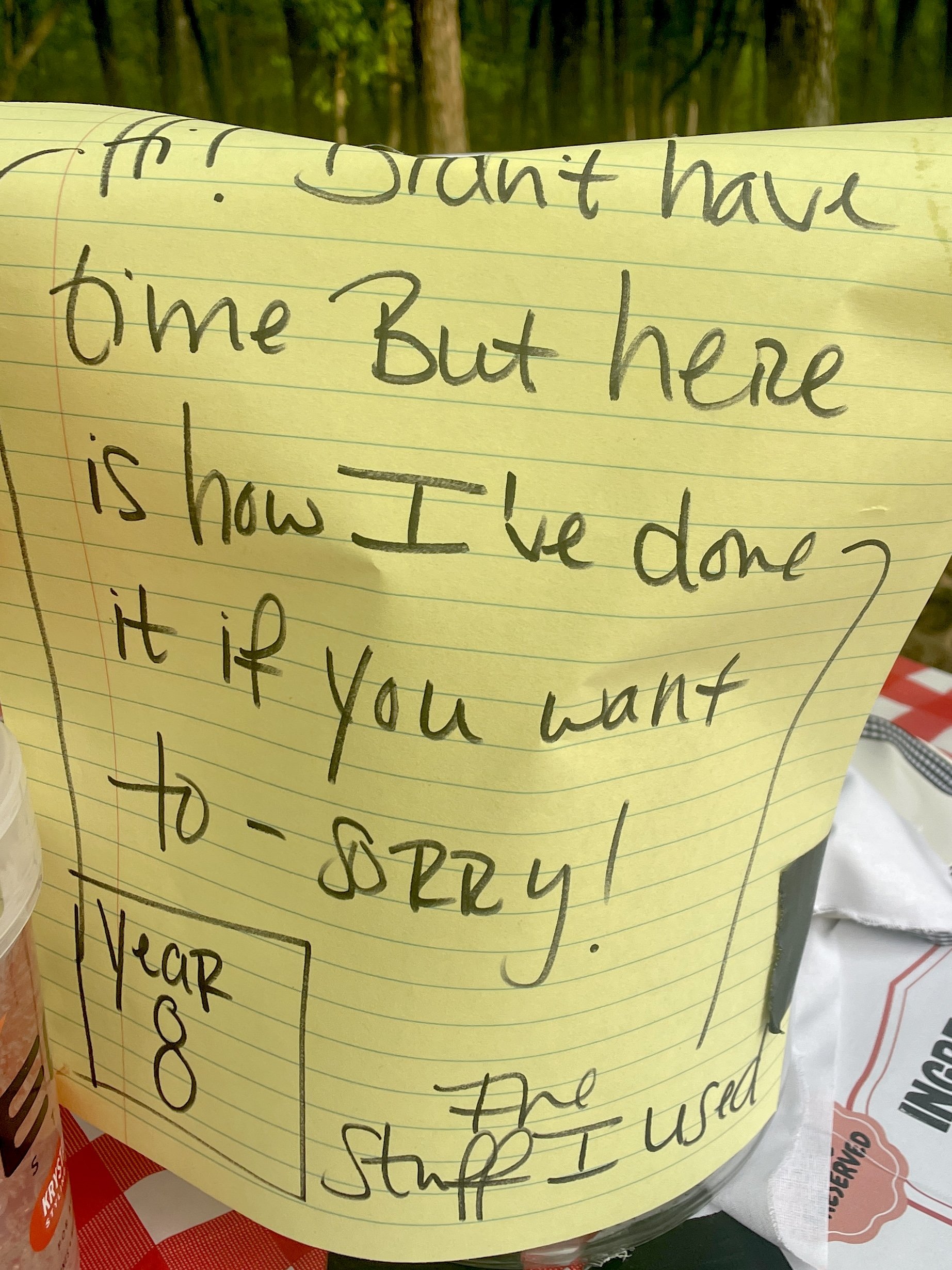

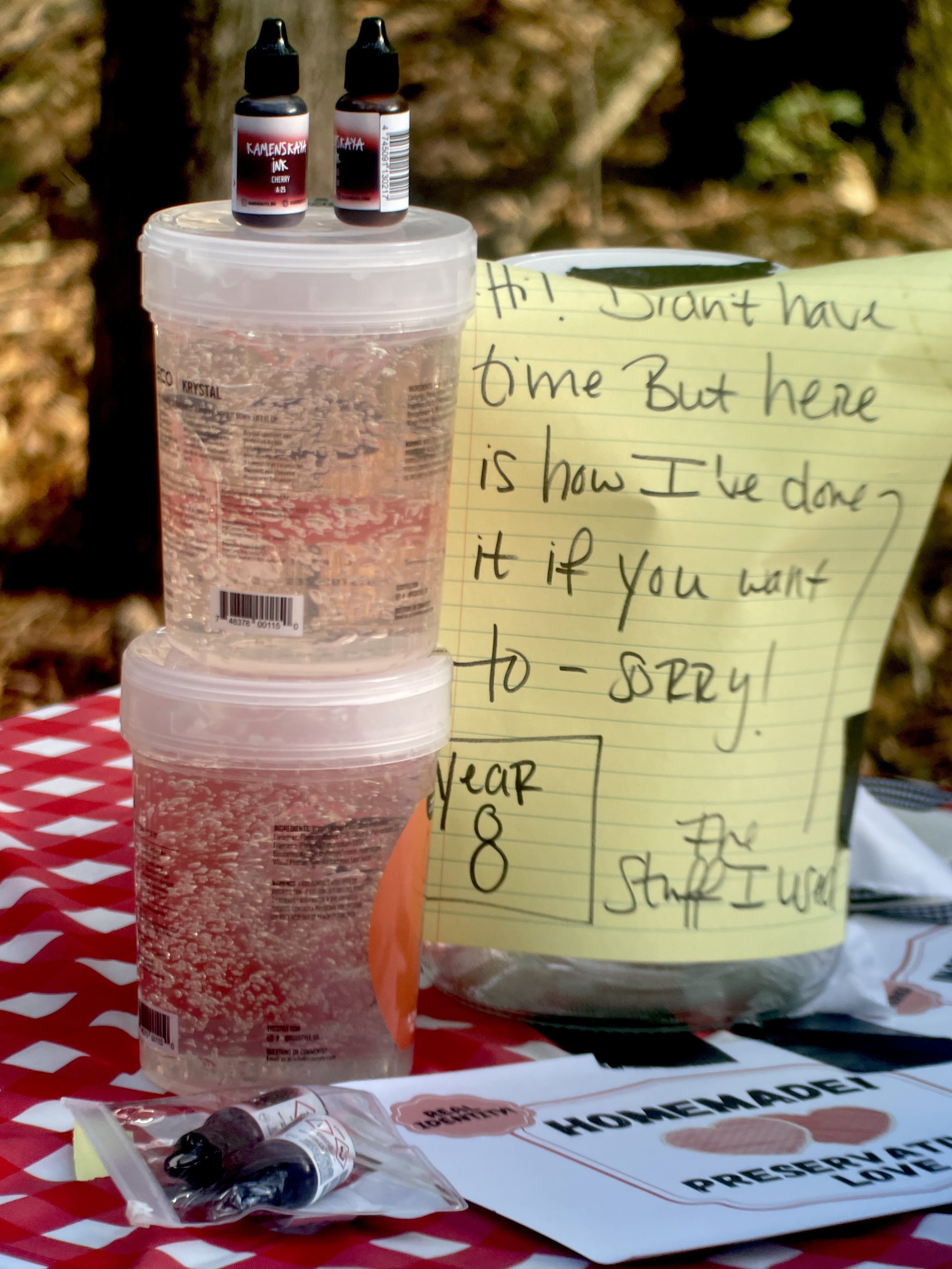

Year 8 Entry

For this entry, the caregiver seems to be providing us with deconstructed preservative love. We at the competition are not into modern interpretations and it is laziness on her part to think someone else should do it for her. Who does she think she is? It is her responsibility. She needs to step up and get it done. Shame.

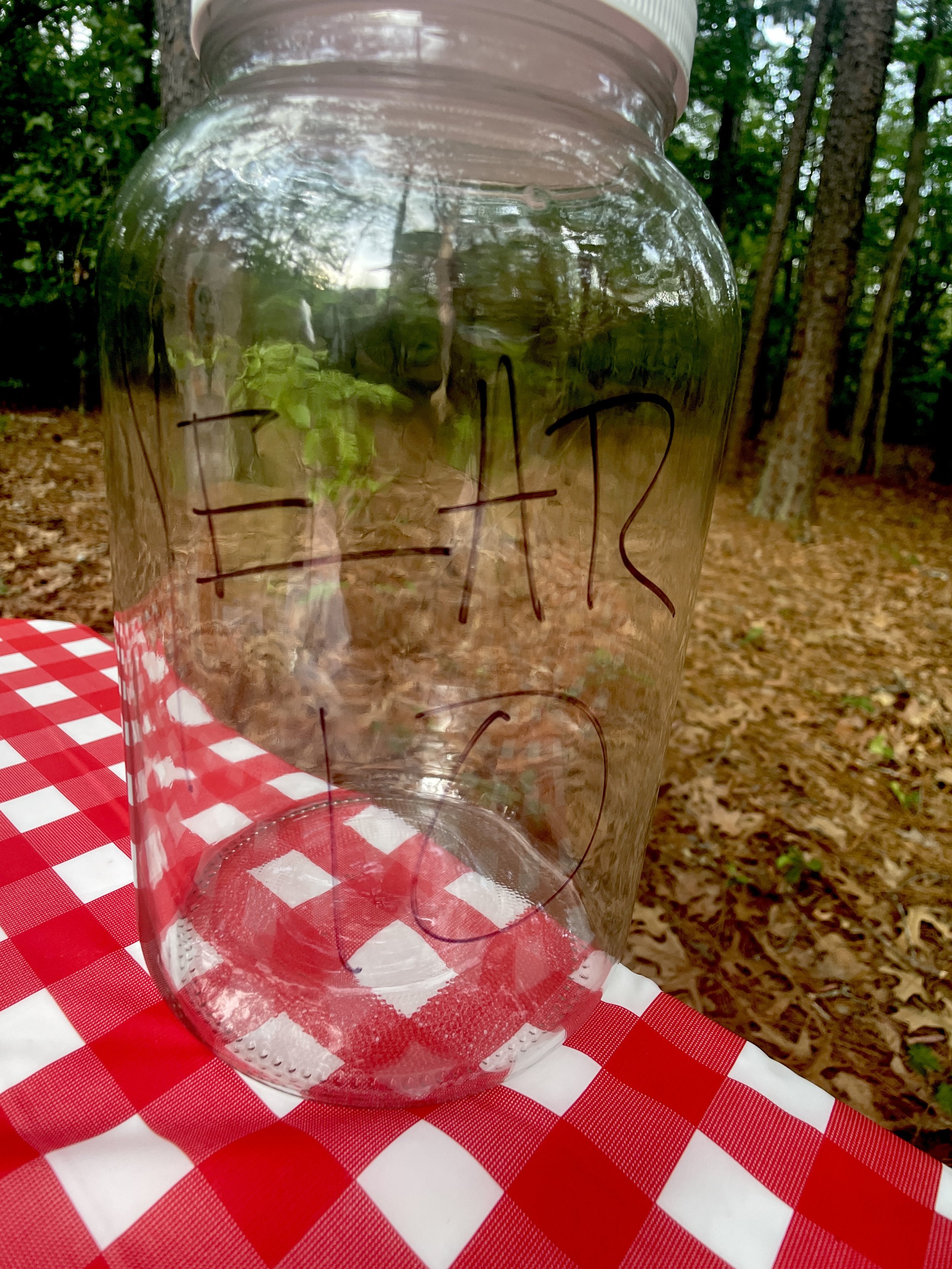

Year 10 Entry

We suppose she should be given bonus points for even getting anything completed. This caregiver is really flailing and it’s sad because she started out so many years ago so strong. We had really high hopes for this one. But this empty jar, with scribbled writing…not impressed. She barely got the jar on the table this year. It’s almost as if she simply didn’t have it in her to do anything. Very disappointing and we are left feeling very concerned about the identity of the loved one she is caring for. If this caregiver can’t even muster up the energy to fill a jar of preservative love, what is she even doing with her life? Bad daughter.

To Date Entries

Entrant # 10,692,4759

Current Ranking: # 8,725,0053

Preservative Love and Holding

In Holding and Letting Go: The Social Practice of Personal Identities, bioethicist Hilde Lindemann explores how identities, rather than being solely individual phenomena, are created and maintained through the social practice of “initiating human beings into personhood and then holding them there” (Lindemann Holding viii). Identities are inherently interpersonal and reciprocal (202, 205).

However, not all holding is equal. “Holding can be done well or badly” (Lindemann Holding x). Holding someone well creates opportunities for them to thrive, while poor holding can be corrosive, diminishing a person’s sense of self, abilities, and capacities. Holding is thus a “real-time, here-and-now morality” (x), a moral practice that offers the chance to bring forth the best or the worst in ourselves and others. We cannot fully be who we are or reach our potential without others seeing us as such (23). We respond to others in ways that seem appropriate based on who they perceive us to be and who we perceive them to be. This interplay between self-conception and external recognition shapes our identities (viii). In this way, we are held by others and, in turn, hold others in their identities.

Lindemann offers a unique understanding of the kind of holding present in relationships with people who have dementia, what she refers to as holding via “preservative love” (Lindemann Beyond 12). Drawing on Sarah Ruddick’s concept of preservative love in the mother/child relationship, wherein the mother seeks to preserve the child from physical harm, Lindemann extends this idea to include protection from “moral harm” (19). In doing so, she addresses concerns around the degree of personhood afforded to individuals with late-stage dementia, where autonomy and moral status are often in question, arguing against the reduction of such individuals to “nonpersons” (12).

Lindemann offers four thoughtful questions to consider when thinking of holding:

“How does this holding go wrong, and what are some of the moral norms that govern it? What does excellent holding look like? Can groups of people, as well as individuals, be held in their identities? What makes it particularly hard to hold people in their identities?” (Lindemann Holding xiii). I will add the question: What does it take to hold someone with dementia in personhood and protect them from moral harm?

For many caregivers, achieving a quality of holding and preservative love that allows for dignity requires significant sacrifice. This can include draining savings, quitting jobs, reducing work hours, or halting career advancement, in addition to various levels of disconnection from partners, children, and social circles (Glenn 3; Karlawish 21, 31; Tolmacz and Pardess 507). With this, I see three intertwined issues that impact the identity of unpaid family dementia caregivers and the holding they are able to provide.

First, in the relationship between these caregivers and their loved ones, the holding of personhood is “one-sided” (Lindemann Holding 3). As the identity of the person with dementia disappears, the unpaid family caregiver holds and provides preservative love for this person, and in doing so, the dementia patient is protected from losing their personhood status (Lindemann Holding 3). However, the person with dementia cannot appropriately hold the identity of the caregiver.

Second, the data shows that isolation is an all too common experience of unpaid family dementia caregiving (Administration for Community Living 30). Many caregivers are left to do this care on their own, often spending day after day providing care within this one-sided relationship. With this, their ability to experience themselves as anything other than caregiver diminishes, when they are so much more than that, if and when given the appropriate holding. Additionally, dementia is a durational illness, during which time caregivers exist in what I am calling an identity void for years, even decades.

With the one-sidedness of the holding between caregiver and their loved one and the durational isolation inherent in this care, I argue that caregivers, within the social and moral practice of holding identities, experience being held poorly, negatively impacting the quality of care, holding, and preservative love they are able to provide. I argue that when caregivers experience being held well, not only are they able to experience themselves beyond their caregiver identity, their ability to hold well and provide preservative love for their loved one expands and increases.

Beyond a representational statement, The All-Country Preservative(s) Love Competition, Entrant #10,692,4759, asks the following questions: If the unpaid family dementia caregiver is holding the identity of their loved one via preservative love, how can we hold the identity of the caregiver so that they may continue to provide the preservative love required to hold someone with dementia in personhood? Do these caregivers need a special kind of preservative love as well that helps them maintain their identities with each passing year? As a social and moral practice, what could it take to hold unpaid family dementia caregivers well?

Works Cited

Administration for Community Living. *2022 National Strategy to Support Family Caregivers*. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022, https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/RAISE_SGRG/NatlStrategyToSupportFamilyCaregivers.pdf.

Glenn, E. *Forced to Care: Coercion and Caregiving in America*. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Karlawish, J. *The Problem of Alzheimer’s: How Science, Culture, and Politics Turned a Rare Disease into a Crisis and What We Can Do About It*. St. Martin’s Press, 2021.

Lindemann, Hilde. “Second Nature and the Tragedy of Alzheimer's.” *Beyond Loss: Dementia, Identity, Personhood*, edited by Lars-Christer Hydén, Hilde Lindemann, and Jens Brockmeier, Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 9–24.

Lindemann, Hilde. *Holding and Letting Go: The Social Practice of Personal Identities*. First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, Oxford University Press, 2016.

Tolmacz, Rachel, and Erez Pardess. "Supporting Dementia Family Carers in Balancing Compassion for Others with Compassion for Self." *Professional Psychology: Research and Practice*, vol. 53, no. 5, 2022, pp. 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000455.

Materials List

Glass Jars

Muslin Fabric

Ribbon

Labels

Hair Gel

Alcohol-based dye

Plastic Folding Table

Plastic Checkered Table Cloth

Black Tape

Yellow Pad Paper

Black Pen

Black Electrical Tape

Printed Labels

Graphic Asset Credits - www.canva.com

Crumpled Paper Heart Shape by Vector Beauty

Empty Vintage Labels by Goichat

Red Round Label by Funtastetive